Everyone.

A friend in the movie business just told me that one of the films he recently worked on is coming out next week. It’s called “Loving”, and it’s a true story about Richard and Mildred Loving. One night several weeks after their wedding in Washington DC in 1958, the police showed up in their bedroom in Virginia and arrested them. Richard was white and Mildred was black and they were convicted of being an interracial couple and sentenced to a year in prison. The judge said "Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. The fact that he separated the races show that he did not intend for the races to mix." Their case eventually went to the Supreme Court and it was overturned ten years later. Those years in the US are often thought of as warm and wonderful times, but I was astonished to find out that a number of states had laws against whites marrying blacks or latinos or Asians up until the Supreme Court case in 1967.

Muriel and Richard Loving

In some ways I guess I shouldn’t be all that surprised. An older cousin and her husband just celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary, and their marriage was a bit of a scandal. You know why? She was Irish, and he was Italian, and although there were no laws against it, both families vaguely hinted that God would not look favorably on such a marriage.

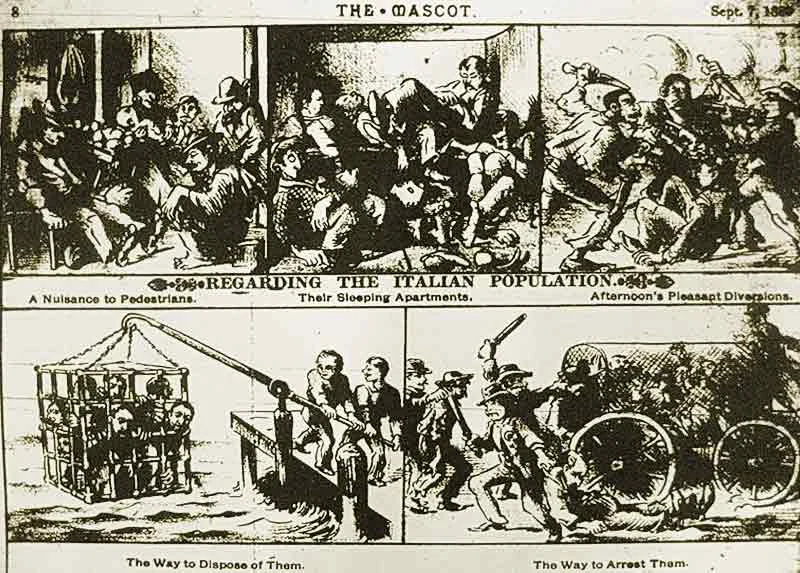

Both cases have something to do with the age-old issue of keeping the ‘tribe’ pure, fear of anyone who comes from a different world, a different culture, a different history, a different world-view. In many cases individuals and whole peoples were and are demonized “They don’t think the way we do”, “all they care about is money”, “they’re all drunks”, “they’re a dirty people”, “they have no respect for our laws”, “they’re all freeloaders and welfare cheats”, “lock your car doors when we go through this neighborhood, kids”, “human life is cheap to them”, ”they are not the chosen people”. And of course there have always been insulting names and terms for the people in those ‘tribes’—be they Italians, Puerto Ricans, Chinese, Arabs, Irish, Poles, or people of different faiths, sexual orientation, races.

I did a little research on the Loving case, and I was happy to discover that the Catholic Church was instrumental in having those marriage laws reversed in the US. But our Church has not been entirely free of a kind of tribalism.

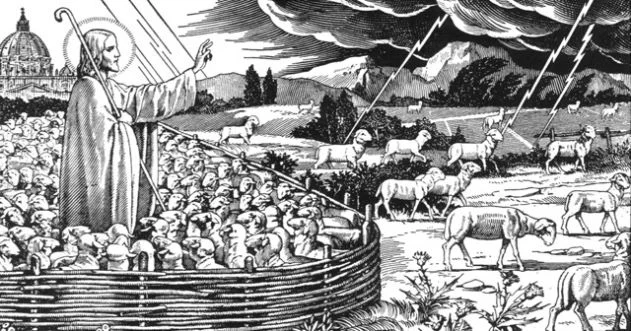

I was a public school kid, and that meant that I got my religious education at CCD classes at our church during release time every Friday afternoon. It wasn’t just us Catholic kids who were released. A bunch of us would be let out of school around 1pm, and two parallel lines of children would form in the parking lot outside the school. Father Murphy would be at the head of one line, and Reverend Springer (who was the minister of the Protestant church) would be at the head of the second one. We weren’t allowed to talk to one another, and when we were all assembled, the two lines of children would follow the sidewalks side-by-side down several streets until we came to this one particular intersection. As we crossed the street, Father Murphy would lead the Catholic kids off the right on our way to the Catholic Church, and Reverend Springer would peel his line of kids off to the left to go to the Protestant church. I’ve often thought that would be a great scene in a movie about life in those days, maybe a crane shot from high above as the lines of children separated in two different directions, a visual metaphor for the division of Christian believers. We were taught that we should never go to a Protestant Church (or a Jewish Temple for that matter), and that God clearly favored us Catholics here on earth as well as in heaven. We were discouraged from getting too close to anyone of a different faith, and there was a vague threat that we would in some way be contaminated by them if we did. And if anyone did stray from the faith and the tribe, it caused great anguish in families, and sometimes great division. That’s how tribes keep their members in check—they employ guilt or condemn or banish those who stray too far from the flock.

I love the story about Zacchaeus. First of all he was short, and I’ve always wanted to be taller. He got up in that tree to be able to see Jesus coming down the road. To the Jews of Jesus’ time, Zacchaeus was probably one of the most demonized and hated persons around. He was a traitor to the tribe because was a tax collector for the enemy, the occupying Romans. Worse, he got wealthy from the job, collecting more money from his own poor people than they owed and keeping it for himself.

But Zacchaeus was a real person, he wasn’t just a stereotype, he had a name, and like everyone else he was desperately looking for what was missing, a deeper meaning to his life. I’m guessing that he wasn’t exactly sure why he needed to climb that tree to get a better view Jesus. But he got up there, hanging on a branch, and Jesus looked up at him, saw the desire in his eyes, immediately called him by name and invited himself to have dinner at Zacchaeus’ house. And that visit caused quite a controversy. What was Jesus doing, going to that guy’s place? How dare he sit and have a meal with that traitor, that sinner, that despicable man? Jesus was challenging the norms of the tribe, risking condemnation and ultimately banishment.

But it was actually nothing new for Jesus. Throughout the Gospels, Jesus is always opening his arms and his heart to the banished, the deplorables, the condemned, the untouchables, the abandoned, the outcasts, the contemptibles, the despised—the people who embarrass us, who are not in our tribe. And the truth is that down through the ages since Jesus walked the earth in the flesh, people have not liked that. How could he? Why would he?

We are guilty of the same fear, the same tribalism, and we while we declare ourselves to be good Catholics, we have often refused to accept the fundamental message about God that Jesus proclaimed, the message from Wisdom: For God “loves all things that are and loathes nothing that He has made; for what He hated, He would not have created.” The truth is, we are often frightened of people and things that are different; we can be racist, petty, selfish and resentful of those who seem to unfairly get more than their share of the pie. We can become vengeful and bitter and downright mean towards others who are not in our camp. We can be as small as Zacchaeus before Jesus embraced him and made him grow. The great scandal of the Christian church is that for centuries we have failed to follow the greatest commandment of Jesus—to love one another in Him. Jesus came to abolish tribal differences, but those who have followed him have done just the opposite. The divisions among Christians—Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox, traditional, progressive—is contrary to his most essential teaching.

But we are also good people, we have the ability to warmly embrace the whole wide world, to let in others who are different; we can celebrate the rich diversity of the universe that God has made. We can follow the vision of Pope Francis who urges us to “go forth to the streets and to the crossroads…to the abandoned, the forgotten, the imperfect, the foreigner…no one excluded. Wherever you are, never build walls or borders, but meeting squares and field hospitals…” We can be a church, he said, "with the face of a mother, who understands, accompanies, and caresses."

One of those CCD marches from my childhood went contrary to the norm. On that particular Friday the children who lined up as usual behind Father Murphy and Reverend Springer didn’t look like good little Catholics or Protestants, whatever that might mean. Instead, we were Superboys, and princesses and witches and hobos and nuns and Frankensteins---and I think a few Beatles---because it was Halloween and we were going to be going trick or treating right after CCD classes. We walked single-file side-by-side on the usual route, our faces covered by our masks and makeup, and when we came to the point of separation, one little Catholic girl named Lauren Berardi was distracted by a wardrobe malfunction of her costume—a cape flew off her back in the wind---and she broke ranks to retrieve it, running into the street. A car was going by at that moment, and the driver desperately tried to avoid Lauren’s running figure, but she hit her. There was an awful chorus of shouts and cries as a crowd of ghosts and goblins and witches watched it happen, watched Lauren get throw across the road like a rag doll. While nearby adults ran to help Lauren, we children stood on the sidewalk, shocked by the violence we had just seen. Within minutes an ambulance appeared, and Lauren was taken away. The priest and the minister conferred for a moment, and then something amazing happened. We all followed them to the Protestant church, which was larger than our Catholic church, and a bit closer. It was the first time I had ever been inside a Protestant church. And all together we prayed to the same God and the same Jesus to save Lauren and to bring her back to health. We were not enemies, after all, when it came to such a difficult moment in life. And for many of us children, it was the beginning of a different understanding about what it really means to be a Christian.

It’s about inclusion, it’s about acceptance, it’s about Jesus calling us all out of the tree, “Zacchaeus come down…I’m hungry and I want to have supper with you, my friend.” Calling us ALL, everyone to the table: rich, poor, black, brown, white, yellow; EVERYONE: women, men, children, male, female, gay and straight; EVERYONE: Jew, Muslim, Hindu, atheist; EVERYONE: Republican, Democrat, Trumpite and Clintonite; EVERYONE: Irish, Italian, African-American, Indian, Korean, Philipino; EVERYONE: criminal and law abider, rebel and obedient; EVERYONE of us who are broken, incomplete, sinners, who are looking for the same thing Zacchaeus desired—the truth about who we are and who we are meant to be.

“Today, salvation has come to this house,” he said to Zacchaeus, and if we embrace our brothers and sisters with the same spirit of inclusion, it will come to ours as well.

Everyone.