Wǒ bù huì shuō zhōngwén. 我不会说中文. I don't speak Chinese.

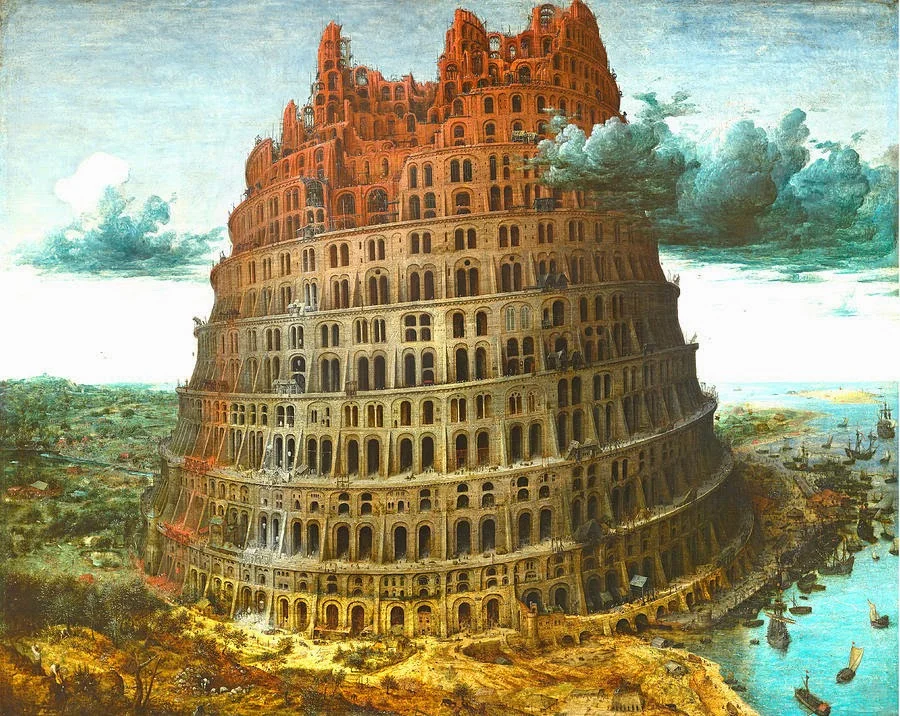

Unfinished Tower of Babel

Wǒ bù huì shuō zhōngwén (我不会说中文). Wǒ bù huì shuō zhōngwén. Wǒ bù huì shuō zhōngwén. I don’t speak Chinese. I was practicing that phrase, trying to memorize it as I began walking along streets that were filled with hundreds and hundreds of Chinese people on motor scooters in the first city I was visiting in that country.

It was hard to hear myself over the unending tooting of horns. When I’m walking in Manhattan, I often get annoyed at the horn-blowing taxis and trucks, but it is NOTHING compared to China. In China each scooter driver uses his or her horn about every 10 seconds, no exaggeration. When I came to my first intersection I was afraid to cross it. They paid no attention to the traffic lights, and you were just supposed to bravely walk across, eyes straight ahead, as they drove around you like a swarm of bees determined to get back to the hive NOW. A swarm of bees with endless and loud honking. Their communication seemed so aggressive and threatening. Get out of my way, I’m coming, watch out, don’t even….they seemed to be announcing.

Wǒ bù huì shuō zhōngwén.

I kept saying it over and over again, the phrase I had memorized to explain my inability to speak their language, standard Mandarin. In retrospect, it was a dumb idea to memorize that phrase. It was perfectly obvious that I didn’t speak the language. I should have memorized something else more useful for my visit, like: “Have you seen my passport?”. Because I lost my passport, in China.

My advice to you: don’t lose your passport in China.

It took me a week and visits to five police stations, two immigration offices and the American Consulate in another city, and except for the consulate, I struggled to communicate with the police and immigration officials who didn’t seem all that interested in helping me. To be honest, the experience kind of soured me. I didn’t like China much, and I found the Chinese to be rude and uncaring. It was easy to generalize, to think of words in my own language that were harsh, unkind and uncharitable to the people of this nation who also seemed to be so aggressive on the world stage.

Armed with a new passport and visa, I was finally able to travel within China, and the language barrier was a challenge. Very few people seemed to know English. When I got to Bejiing, a huge city of 24 million people, I took the subway from the airport, and when I got off I relied on the GPS on my phone to find the hotel that I had booked online. The scooters were everywhere there too, horns incessantly honking, and I was dodging them as I followed the map on my phone. It took me a while before I realized that the GPS was confused. It was sending me in virtual circles or down dead-end streets. Not matter which way I went, I couldn’t find the hotel. I stopped a bunch of times and tried to get someone to help me, Wǒ bù huì shuō zhōngwén, but no one wanted to talk to me. They seemed to purposely ignore me.

Exhausted after about 2 hours of walking with a pretty heavy bag, and assaulted with those darned scooters and their horns, I felt really alone. I sat down on some steps and my eyes started to fill up. I must have looked miserable. An elderly woman holding a bag of vegetables was walking by and she stopped for a moment, looked over at me and then approached. She had a very wrinkled, kind face. She smiled at me, and started speaking to me in Chinese. Wǒ bù huì shuō zhōngwén, I said, looking up at her. She put her hand on my shoulder, tapping it gently like she wanted me to know that she understood how I felt. Then she gestured to me to get up and follow her, and when I hesitated, she was insistent in her tone and her gestures.

We walked a block or two together, and she brought me to a street-level office. She opened the door and called to a young man who was behind a desk. He came out, she spoke to him, pointing at me, and I could tell she was urging him to take care of me. Within a few minutes there were five others out on the sidewalk with us, and when I showed them the GPS and the hotel name, they became this… task force. They had a lively discussion, went to work trying to find the location on their own phones, and one guy retrieved a city map from inside the office. They seemed to identify the correct location for the hotel, and without warning a scooter appeared. A young man gestured to climb on behind him, and he grabbed my bag and put it in between his knees. The elderly woman smiled and waved at me, and the rest of the task force laughed and bowed in my direction. We were off.

It was weirdly intimate as I held onto a stranger’s waist, and it struck me that I was suddenly one of them navigating through and within this sea of honking scooters. It was an entirely different perspective, and I began to ‘get’ their use of the horns. There was no animosity or aggressiveness about it, as I had assumed. In fact it felt more protective and considerate, more like “please watch out”, “ I don’t want to hit you”, “take care” rather than “get out of my way, you moron” which I have actually heard shouted along with the horn blast in Manhattan.

When we got to the hotel, the driver helped me inside with my bag. He stayed a bit to make sure I was OK, and then he bowed slightly to me, smiling, and left.

Up in my hotel room, looking down at the street teaming with scooters and people rushing in all directions, I thought about my ‘rescue’ and how we had communicated on an entirely different level. And I began to think maybe I was wrong about the people and the nation I was judging so harshly.

I was reading that there are about 6000 languages in the world today, and only about half of them are predicted to survive to the end of the 21st century. Technology is enabling a kind of linguistic and cultural homogenization around the world and if you do any traveling you certainly are aware how much English is a part of that trend. Some people think that such homogenization or blending or intermixing will mean a loss for the culture of our individual nations, and they think we should do everything we can to preserve our languages which are embedded with our heritage, our truths, and our perspective on life.

World language map

On the other hand the differences enshrined in the languages that distinguish us have a long history of sparking bloodshed. Since the fall of the Tower of Babel, humans have been at one another's throats over ethnic, cultural, national, religious and other differences that our languages represent. Maybe we would have more peace in the world or greater human understanding if everyone spoke the same tongue.

But I’m not so sure that’s going to happen any time soon, and I’m not so sure it should. I doubt that the Chinese will abandon a language that is embedded with the wisdom of their ancestors, and I think the same is true of those of us who speak English or any of the other major languages of our world. And a homogenized linguistic world may not be the way to true peace.

On the day they called Pentecost, 50 days after Easter, friends, disciples and apostles of Jesus experienced a new language that marked the dividing line between the ministry of the Lord and the ministry of the Spirit. It is said that over 3000 people who couldn’t understand one another’s languages--the languages of the Parthians, Medes, Elamites, Cretans, Arabs, Romans, Jews, the languages of the inhabitants of Mesopotamia, Judea, Cappadocia, Pontus, Asia, Phrygia, Pamphylia, Egypt, and Libya—those 3000 people were blessed with a new language that was more inclusive than their own. On Pentecost, the birthday of the church, 50 days after the incredible phenomenon of an empty tomb, the Holy Spirit—the powerful love of Father and Son--communicated the only way to true peace in the world.

It was through a new language of love.

Unlike our own languages that sometime sound like arrogant, angry, mistrustful, aggressive horn-blowing, the language of the Spirit communicates love, joy, peace, trustfulness, kindness, goodness, gentleness, patience, and self-control.

The language of love is paradoxically a language of silence, a language that speaks to a listening heart. The language of the Spirit invites us to pay attention to one another, to listen to the hopes and dreams and desires of our brothers and sisters. The language of love helps us see through the misbehaviors, selfishness and sinfulness of the people all around us and all around the world and even within ourselves. The language of the Spirit always breaks down the barriers between us, reveals our fundamental relationship as children of God.

But wrapped up in our selves, we deliberately choose a lesser language.

We choose a language that divides us rather than unites us as brothers and sisters. We choose a language that makes us deaf to one another, deaf to the fears, doubts, concerns, and worries of our brothers and sisters. We choose a language that enables us to label one another as Jews and Christians and Muslims, as gays and straights and transgender, as republicans and democrats, liberal and conservative, traditional and progressive, alt-righters and bleeding hearts. We choose a language that enables us to write one another off as narcissists, rednecks, commies, racists, terrorists, anchor babies, papists, infidels, heretics, egotists, deadbeats, trust babies, trolls, elitists, hacks, bigots, misogynists, haters, and dozens of others.

The Spirit came upon the earth with a new language on the 50th day after Easter, and it brought everyone together as a family of brothers and sisters---young, old, rich and poor, Greek, Jew, woman, man, black, brown, yellow and white----and they all understood one another. And from that day forward they knew when the Spirit was with them---whenever divisions ceased, whenever selfishness was overcome, whenever loneliness was dispelled, they felt the Spirit making them one body and one spirit in the Lord Jesus.

And the same is true of us. You know, this church of ours was never meant to be a private affair, it was never meant to foster anonymity or separation. This church of ours is meant to be a real community, a true family, where we share the most important of things with one another. It was not meant to be an obligation, or a duty, or a chore, or a guilt trip. It was never supposed to be a place where people were strangers to one another, barely looked at one another, treated one another with only the minimal courtesy. And I hate to say it but lots of Catholic churches are just that---and for many people in them the experience isn’t a whole lot different than going to the library or the lecture hall or the gym. You come and do what you have to do, and you get out.

That’s not what the church is supposed to be, and if the Spirit is alive in the church, that’s what it will never be. But you’ve got to want the Spirit, and you’ve got to be open to the Spirit, and when you are, with the Spirit in our midst, it is a collective love, a new language that is evident for all who can see and hear.

Wǒ bù huì shuō zhōngwén. I don’t speak Chinese. I don’t speak English. I speak love, I choose to listen with love, I choose to love all my brothers and sisters, no matter what they speak.

So, let’s pray for the Holy Spirit to come rest in our individual hearts. Let’s pray for the Holy Spirit to truly come make us a family of love across the whole earth, from here to China. Let’s pray….come Holy Spirit fill our hearts, our minds, our souls that we may love one another and in our love bring the love of Jesus to all we meet and serve, and we say this prayer as one body in Jesus, Amen.